Catherine Onyemelukwe, a white American, went to Nigeria with the Peace Corps in the early 1960s and stayed twenty-four years. Now based in the U.S., Catherine serves on the U.S. Committee for UN Women, She is an activist for racial justice in her community and her Unitarian congregation.

Catherine’s memoir, Nigeria Revisited—My Life and Loves Abroad, kept me turning pages as fast as a good novel. It also showed me a different world. Yet, I found some facets delightfully familiar when Catherine used some of the very persuasion, consensus-building and communication skills I teach, coach and write about.

I wanted to know more, so I asked Catherine for an interview. Her answers to my questions are as interesting as her book.

MEA: In the 1960s, racial tensions in the U. S. were running high. How did you expect your parents to react to the news that you were engaged to a native Nigerian? And how did they react in fact?

CO: I expected my parents to accept my decision without prejudice, though I admit I was a little worried. But they did! I was grateful. I think they had raised me to feel comfortable living in a different culture and with people of another race, so I wasn’t surprised.

My mother said she had one question – was he Christian? She had taken a class about Nigeria at the University of Cincinnati so knew that half the country was Muslim.

I was a little surprised by my father’s sense of “You show them you can do what you want!” about people in our conservative Northern Kentucky town.

MEA: What did your fiancé Clement (“Clem”) expect from his prospective in-laws?

CO: I think he was worried, unlike me. He had lived in England for nine years, but hadn’t been serious about any English women to the point of meeting her parents. And he didn’t know many Americans. I think he expected a little hostility.

MEA: Sounds like Clem was pleasantly surprised. Some white American parents would have disowned you over this engagement. But yours behaved as if you had married the boy next door. What do you think accounts for their exceptional behavior?

CO: My father had come to the U.S. from Germany in the early 1930’s. He met my mother, a mid-Westerner, in New York. The ideas of moving to another continent (for him) and marrying someone from a different culture (for her) were familiar to them.

MEA: How did you and Clem expect his parents to react to the engagement? And how did they react in fact?

CO: Clem knew his parents would not be pleased. They had celebrated his return from England without a foreign wife! They knew of British wives who had come to Nigeria, and then after having one or two children, left Nigeria, taking the children with them. They were concerned that I would do the same.

Clem had arranged for me to meet his parents before I knew we would marry (though he already suspected that we would). By the time I knew we would marry, they had already absorbed the shock. They saw quickly that I was learning the Igbo language and accepted some customs that were important to them, so in the end they were very happy with our marriage

MEA: In many ways, you embraced Clem’s culture and came to love it. However, you rejected some traditions; you stood up for equality between spouses. In doing so, you used skills I teach and coach, such as replacing argumentative statements with questions. For example, as to the marriage vows, you asked Clem, “Why should I promise to obey you? Are you going to promise to obey me?” Did this use of questions come instinctively, or did you learn it?

CO: I believe it came instinctively to me. I don’t recall learning that using questions was helpful in coming to an agreement. It made sense to me, so I did it!

MEA: When you were courting, what did you see in Clem’s personality and background that suggested he would accept a more egalitarian marriage than most Nigerians?

CO: I’m not sure I did see that initially. But I could tell that his years in England had familiarized him a little with women’s rights and expectations of marriage. But remember this was the early to mid-1960’s, and women’s lib had not yet taken place. So I didn’t expect as much as I did later after a year in the U.S. during the mid-1970’s.

MEA: What were some things you began to expect after that trip to the U.S., and how did Clem react to your new expectations?

CO: I expected to be listened to more than I had been. Clem is still getting used to this idea!

MEA: I have observed that we sometimes cut foreigners more slack than those of our own nationality. We may excuse, as cultural differences, things that would offend us if a fellow American said or did them, even if we don’t know exactly what those foreign cultural differences are. But we may not realize that “offenses” committed by someone of our own nationality can stem from unrecognized intra-national cultural differences such as gender, region or generation.

Did knowing that you and Clem had cultural differences make resolving disagreements easier or harder than if you had married an American?

CO: I think it made it easier. We have tried to talk about cultural differences after a disagreement is resolved, but rarely as we’re getting into the disagreement when emotions are high! But I have to say that he sometimes says I should excuse his behavior because “I’m an African!” I usually laugh!

MEA: So are you saying that, during the disagreement, when emotions are high, there is a subconscious realization of cultural differences that helps you reach that resolution? That you do cut each other more slack?

CO: Yes, for sure.

MEA: Putting the shoe on the other foot, have you ever done something, and Clem said, “I’ll excuse that behavior because you’re an American”?

CO: You’re kidding, right?

MEA: You lived in the Igbo territory in east Nigeria, the region that became “Biafra” during the civil war. What was hardest about coping with that war?

CO: The uncertainty was the hardest. When the war started many of us on the Biafran side felt fairly certain that justice was on our side, we would be supported, and would succeed. For safety, we moved from Lagos to Clem’s village. But after six or eight months living in the village, refugees came into our town of Nanka. I recognized that Biafra was losing territory more quickly than the government was admitting. That and news on VOA and BBC led me to suspect that the news we were hearing from the Biafran government might be embellished.

MEA: And those things, the refugees and what you heard on VOA and BBC, convinced you to take your children and go to the U.S. for safety. Eventually, you felt safe enough to return to Nigeria. How would you describe feelings and relations between ordinary people of the south and north shortly after the war? And today?

CO: The head of the Nigerian government at the time, Yakubu Gowon, made an effort to reconcile the differences and bring the rebellious easterners, mainly the Igbo people, back into the country. I believe he was fairly successful. I did not feel afraid. There was no warlike atmosphere in the country after the war, although I didn’t go back until six months after the war ended.

Today there is a very small but vocal group of Igbo people who think there should be another attempt at secession. But for most people the idea is long gone. Northerners and southerners are able to live together and work together peacefully.

MEA: In your book, Clem comes across as a reserved sort of person. Yet, the memoir describes very personal details about your marriage, family and personal life. What ways of relating and communicating with each other helped him accept publication of the memoir?

CO: I was gentle with him. I gave him the completed memoir to read. I explained that he would find some events in my life he hadn’t known about. But I wanted him to remember that we were now together and happy to be so.

He took the memoir with him on a business trip, and when he returned three weeks later, having read it, I asked if he had any questions for me. To this day, I’m not sure what has made him accept and be proud of the memoir with all its revelations!

MEA: That’s a beautiful example of one of the principles I teach people: Slow down to get there faster; give people time to let their knee-jerk reactions settle down and to get their minds around new ideas. So that, too, came to you intuitively, right?

CO: Yes, you are right.

MEA: What three things would you like my readers to know about present-day Nigeria?

CO: 1. There is certainly a functional democracy in Nigeria today. The next election in 2019 is expected to go smoothly.

- Income inequality, perhaps even worse than in the U.S., is an issue. But poor people in Nigeria are not starving, although the people displaced by Boko Haram[1] are in difficult straits right now.

- The low price of petroleum has hit the country hard. Too many years counting on $100+/barrel price let the government ‘off the hook’ about diversifying the economy

MEA: I could easily ask more questions, but that’s enough for now.

Thanks so much for sharing your remarkable experiences with me and my readers. You’ve given us much to think about, and it will stay with me for a long time.

CO: Thank you so much, Margaret. You asked good questions!

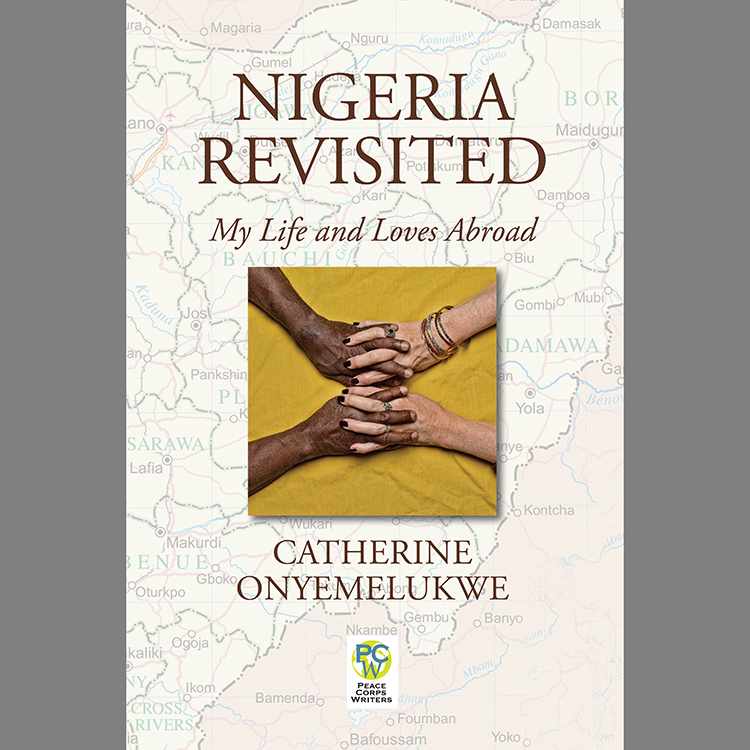

Catherine’s memoir, Nigeria Revisited, is available from Amazon in both print and Kindle editions.

[1] Boko Haram is a Nigerian based, extreme Islamist group whose Jihad focuses on forbidding anything even remotely associated with the West.

I am hosting a young Nigerian man who,having achieved two Master’s degrees in Chemistry and in Environmental Science,is now going to pursue a PhD in a related field. Also he is planning to have a Nigerian wife as his mate here in the US. He has duel citizenship. His loyalty to the US seems strong although he questions the current political scene. He is from Kano in the North. I found your interview with

Catherine Onyemelukwe so interesting especially since I also was in the Peace Corps in Peru in the 60s.

I am so sorry that this comment didn’t reach me for moderation sooner. Glad you enjoyed the interview and that you plan to get acquainted with Catherine. Be sure to tell her “hi” from me.