[This article is adapted from a program I presented for Women’s History Month, March 2013.]

My job is training people in what, for church groups, I call consensus building skills. But I’m going to let you in on a little secret. These are the same skills that I call “persuasion” or “negotiation” for business people. But church people can hear “persuasion” or “negotiation” and think “manipulation” or “exploitation.”

So, whomever I’m training, I start with the difference between two different systems of negotiation. Everybody already knows the first system, which I call “number line tug-of-war.” Let’s say Sammy the Sailor wants to sell his boat, and I want to buy it. Sammy asks for $30,000 and stands on a number line at the $30,000 point. I offer $20,000 and stand on the number line at that point. Now Sammy and I grab the two ends of a rope and try to pull each other closer on that number line. It’s a win-lose contest. The more one of us gains, the more the other loses.

Number line tug-of-war has its uses, but I describe it more for contrast with the system I actually teach. In our system, Sammy and I talk about the interests behind the numbers, what we’re really trying to accomplish. If Sammy wants the $30,000 to buy a used RV, and I just happen to own an RV I don’t want, and Sammy likes it, we’re both happier with a win-win swap in which no money at all changes hands.

That’s an easy example, just to illustrate the principles of the two systems. In training, we then go into more difficult situations and the many skills that get us a win-win result, when possible, and a reasonable compromise, when compromise is necessary.

As trainees use these skills in practice exercises and experience win-win consensus, they have different kinds of epiphanies. For a lot of men, and some women, the epiphany feels like the one where St. Paul was on his way to persecute the Christians and God knocked him off his horse. “Wow! Number line tug-of-war is not the definition of negotiation. There’s a totally different approach I never would have thought of.”

For a lot of women, and some men, the epiphany feels more like a huge sigh of relief. “You mean I don’t have to grapple on that number line? I not only don’t have to, but I can actually meet my needs better if I don’t? Aaah.” I’m not saying these people don’t have anything to learn about consensus building. They still need the detailed skills, but the skills don’t feel so foreign to them.

Which brings us to a bigger picture. Everyone has two opposing needs in relation to others. We all want some measure of status—to be independent, distinct from others, and to compare favorably with others. The desire for status manifests itself in hierarchical relationships and competitive interactions. Little boys at play often establish a leader by telling other boys what to do and seeing whose orders the group follows. And they like to play competitive games, like sports.

Everyone also has a need for connection with other people—to feel that they’re similar to others and fit in with a group. The desire for connection manifests itself in egalitarian relationships and collaborative or cooperative interactions. The little girl who tries to boss other girls around can become a pariah. Instead, girls decide together what they’re going to play; they seek consensus. And what they play is often non-competitive, like playing grown ups going shopping or having tea.

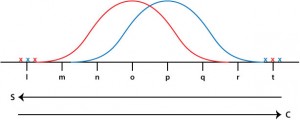

We all want some status and some connection with others, but people differ in how much of each they want. I’ve shown this on the Figure below with two scales running in opposite directions. They’re inversely proportional. S, for status, increases from right to left. C, for connection, increases from left to right.

So if Pat feels comfortable at point n, and Chris feels comfortable at point p, Pat feels a greater need for status, and Chris wants more connection. But they both include status and connection in their relationships with others.

Many factors—such as nationality, regionality, family customs, temperament and gender—influence these priorities. So if I want to show two groups of people who differ by one factor, I don’t show them as two points, but rather as two overlapping bell curves. The curves are conceptual, not mathematically precise. I don’t know how tall or wide they are, but I know they’re overlapping bells. Plus, there are extreme individuals from both groups who are off the curves, as indicated by the red and blue Xs at the far ends.

The red and blue could represent Americans and Japanese, or Californians and New Yorkers, or for present purposes, men and women.

On the far right of the blue, or women’s, curve at r, we find women so uncompetitive that they habitually sacrifice their own needs and give in to others just to avoid dealing with differences.

Moving left on the blue curve, we find women with increasing needs for status. The majority, between points o and q, want significant control over their own lives, but don’t have a strong interest in power over other people. They don’t mind letting someone else take control when the issue just doesn’t justify the effort of making a contest out of it.

At point p we find a woman who needs it explained to her that, if she asks her spouse to call her when he arrives at an out of town destination, men can see that as a control thing, a check-in, like one would check in with the boss. Never would have occurred to her. But when it’s explained, she can understand the concept, even if she doesn’t agree with it.

On the far left of the blue curve at n, we find women who are more competitive than some men.

On the far right of the red curve, at q, I envision feminist men, men who accept what the sociologists and economists tell us—that the more a society empowers its women, the more everyone in that society thrives. We find a man who doesn’t need to be asked to phone when he arrives out of town. He’ll call on his own because he wants to connect with his wife as much as she wants to connect with him.

The majority of men, between points n and p, can see up-down interpretations of things that women might not see, like phoning as a check-in. But that doesn’t mean that they try to “win” every interaction. They don’t want other people pushing them around, but they don’t always try to control others.

When the wife explains that she wants him to call when he arrives, not to check up, but to connect with him as an equal whom she misses and wants to know is safe, he gets it. But, because he also gets how his male companions see it, he tries to phone her in private so they don’t tease him about checking in.

The farther to the left, the more people not only want to control their own lives, but also like to control others. On the far left of the red curve, around point m, we find men who feel that every interaction and every relationship is hierarchical. You’re either one up, or you’re one down. You’re either controlling the other person, or they’re controlling you. You’re either a winner or a loser. Everything’s a contest, and he tries to win every contest. Equal does not compute.

Dr. Deborah Tannen took part in a phone-in radio discussion about which spouse was the boss in marriage. A woman called in to say that, in her marriage, there was no boss. She and her spouse decided things together as equal partners. Next, a man from point m phoned to reply, “That’s what’s wrong with you women. You want to control us.” To him, if she wasn’t content to be controlled, she must want to do the controlling. Those were the only two options.

Now if the norms we see in typical groups of women and men, respectively, held equal prominence in our society, we’d have a good balance between egalitarianism and hierarchy, and between collaboration and competition, all of which have their place. But those two sets of norms are not equally represented because, for millennia, men have devised and dominated most social structures. Governments, academia, and most businesses and religions are unduly hierarchical and competitive.

So what seems normal in our society is skewed to the left on the scales. Hence the title of this program: “Been There, Haven’t Done That.” We’ve made great strides in rights for individual women, but we haven’t gained equal prominence of women’s egalitarian social structures and collaborative ways of interacting. This is why my new trainees—of both genders—always know about number line tug-of-war, but may not have seen many examples of win-win consensus building.

Moreover, the highest profile people, those with whom others compare themselves and whom they seek to emulate, are often competitive men at the tops of hierarchical institutions.

Though most boys and men are somewhat competitive by nature, the leftward skewing of society’s concept of normality, and the prominence of competitive alpha males, puts a lot of extra pressure on guys to try to “win” interactions with others; to at least sometimes be one up, to at least sometimes be the one in power or control, to out rank at least someone.

My nephew, as a little tyke, told his mom that his big brother got to boss him around, and she and Dad get to boss big brother around, “but who do I get to boss around?” Fortunately, he’s outgrown this. But many of the problems in our society are related to excessive needs to out rank or control, to win out over others.

The most common profile of an incest perpetrator is the guy who feels like he’s on the bottom of the heap at work, totally powerless and controlled by others. So he goes home and exerts power over the only person he can control, a child who’s in no position to resist because that child depends on him.

All forms of abuse are about power and control. So is rape. Road rage is about never letting someone else “beat” you. The dysfunction in Congress stems from an excessive need to make everything a contest and win every contest, even if it hurts.

There’s abundant evidence that empowering women, as by education and ready access to birth control, raises the quality of life for an entire society. Viewing it another way, population growth exacerbates every other major problem: economic downturns, poverty, crime, pollution, depletion of non-renewable petroleum, you name it.

Men don’t have to support equal empowerment for women out of the goodness of their hearts. It benefits them, too. Yet, we witness extremely strong resistance to equal empowerment in patriarchal societies.

The hierarchical view of life extends beyond personal relationships to the status of entire demographic groups. And in most societies, even the man on the bottom of the heap at work can at least feel that he out ranks women.

Our entire culture is permeated with direct and indirect signals that men out rank women. If someone tells you they don’t believe this, ask them to imagine their son growing up in a world where God is female, our species is called “woman” or “womankind,” we routinely call men “boys” in contexts where we wouldn’t call the women “girls,” when we play cards, the Queen outranks the King. How would that boy turn out? And how would girls turn out?

As I’ve mentioned in previous programs, our conscious thoughts are only a small part of what goes on in our brains and what actually drives our behavior. People sense, whether consciously or not, that, when women are educated and have birth control, thus are free to engage in gainful employment, they take control over their own lives.

But if you’re programmed to feel that a person, or demographic group, either controls or is controlled by another, then if women gain control over their own lives, that feels like men lose. Just as, on Dr. Tannen’s talk show, the wife who wasn’t controlled by her spouse must have controlled him, if women, as a group, gain control over their own lives, that feels like they switch rank and supplant men. Equal does not compute.

Now, I’m not naïve enough to believe that, if only our view of normality would to shift to the right on these scales, there’d be no more abuse, no more rape, no more legislative dysfunction, no more “keep ‘em barefoot and pregnant” agenda. But I do believe there would be less of those things because we’d view them as more extreme, farther from the norm. And there would be less pressure on men to outrank or control someone.

I do believe our view of what’s normal is slowly shifting into better balance. Over the decades, women have improved their status. So their ways of doing things are gaining exposure and a greater feeling of normality. A long-time woman minister told me that, when she first started, the atmosphere in her professional organization was all about competition. But as more women have joined the clergy, that organization has become truly collegial and supportive.

So, aside from what the economists tell us, another reason society benefits as women gain equality is by facilitating a balance between competition and collaboration. Equal status, not only for women per se, but also for their collaborative way of interacting, facilitates understanding and use of win-win consensus building skills, skills that often work better for both parties than number line tug of war.

Though the improving status of women could eventually bring about this balance, we can speed up the progress. For example, when we see Sammy the Sailor make a creative swap of his boat for the RV he wanted, instead of grappling on a number line, we can hold that up to others as a smart move, a success.

Or if we notice that Barbra the boss guides and collaborates, instead of commanding and controlling her employees, and it works, we can express our admiration and respect for her. That speeds up the progress toward balance by raising the visibility and normality of egalitarian and collaborative values.

So I’d like to encourage you all to look for examples of egalitarian values and collaborative interactions that you can hold up for others, especially young people. And I’d love to hear from you about what results you experience.